Few, if any, alcoholic beverages have the same kind of depth of history and culture as absinthe. In some form, drinks containing wormwood, the main herbal component of absinthe, have been produced since the beginning of recorded history. And in the nineteenth century, it was enjoyed throughout Europe, even becoming the drink of choice for the entire French nation. Yet despite its long history, absinthe is a drink shrouded in mystery for the majority of the English-speaking world.

Absinthe is a strong, bitter, distilled spirit, which is derived from the plant grand wormwood (a hardy perennial growing wild throughout Europe) and includes other herbs like anise and fennel. The exact proportions of each herb depend on the distiller’s recipe and the region in which it is produced. For instance, in France and Switzerland, distillers prefer their drink with a high concentration of anise, while in the Bohemian countries like the Czech Republic, producers such as Hill’s have a history of distilling absinthe with a low-anise flavour. The latter, low-anise absinthe is also preferred in North America, particularly because of its versatility as a base for cocktails.

Absinthe is different from most spirits in that it is bottled at a high proof (from 45-75% ABV) but is commonly drunk diluted with water, a peculiarity that may be the result of its apparent origins as a medicinal tonic. Indeed, the strength of the drink is legendary, and led to an interesting French ritual in the nineteenth century featuring the use of special water fountains to dilute the drink, as well as its popularity in Czechoslovakia during the rationing of the Second World War.

Although its exact origins are uncertain, it is known from a surviving papyrus that wormwood was utilized in medical treatments in ancient Egypt, as far back as 1550 BC. The ancient Greeks also favoured it for this purpose, using wormwood extracts and its leaves in medicinal concoctions. As well, they are supposed to have drunk a wormwood-infused wine called absinthites oinos. Even today, wormwood is used as a natural remedy, as it is considered to be anti-parisitic, an appetite stimulant, and anti-malarial.

In its modern form, absinthe is thought to have originated as a medicinal tonic in the Alps of Switzerland and France during the eighteenth century. Its real popularity in those countries, however, was brought about by the use of absinthe as an anti-malarial treatment for French troops in the 1840s. Upon their return to France, absinthe became the drink of choice throughout the social classes, and was widely available in bars, cafés and cabarets. By the 1860s, it had become so popular in France that 5 p.m. was called l’heure verte, or “the green hour”, after the drink’s green colour. (Its green colour is also responsible for the drink’s nickname, “La Fée Verte” or “The Green Fairy”.)

The fall of absinthe in France came about in the early twentieth century with a campaign for prohibition. Campaigners demonized the drink as a hallucinogenic, and by 1915 it was finally made illegal not only in France but in several European countries and the United States.

In Czechoslovakia, there are records indicating the production of absinthe from at least as early as the 1860s. This is not surprising given the fact that there has been a long history of Central and Eastern Europeans enjoying wormwood-based alcoholic beverages. These include pelinkovak (a Balkan drink that is the national liqueur of Slovenia), unicum (Hungary), piolunowka (a Polish drink dating back to the seventeenth century), as well as wormwood-based wines in Bulgaria and Romania.

Western Europe’s restrictions on the production and consumption of absinthe never reached Czechoslovakia, meaning that Czech distilleries were able to openly produce absinthe in the early 1900’s. Czech literature from the period attests to the drink’s popularity, which only increased with Nazi rationing during the Second World War (a result of absinthe’s high alcohol content).

With the end of the war, however, came the rise of communism and the nationalization of Czech distilleries. Absinthe production came to a complete halt until the 1990s and the fall of the communist regime, when Czech distilleries began to produce the drink again. It has since become extremely sought-after in the Czech Republic, England and Canada. For suggestions on how to prepare absinthe, please click here.

Absinthe in Art

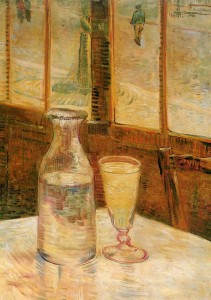

Absinthe was especially favoured by Parisian artists and writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and there are many paintings extant today that contain references to this drink. These include Edouard Manet’s The Absinthe Drinker (1859); Edgar Degas’s L’Absinthe (1876); Vincent Van Gogh’s Still Life with Absinthe (1887); and Pablo Picasso’

s Absinthe Glass (1914). It therefore came to be widely associated with artistic culture from this period, as well as with artistic creation and inspiration, an association that continues to this day.

Artists such as Vincent Van Gogh, Aleister Crowley, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Charles Baudelaire and Oscar Wilde are just a few of the cultural leaders of that time who are known to have enjoyed absinthe. Some well-known contemporary artists who have since fallen under absinthe’s spell are Johnny Depp, The Sugar Cubes, John Moore (guitarist of the Jesus and Mary Chain), and Marilyn Manson.